In recent times, one African engulfed in the sociological debate, and sometimes philosophical too, over what may be considered beautiful, is Lupita Nyong’o.

The Kenyan actress has been on record in the last five or so years, speaking and writing about what she feels are the ills of a world in which Eurocentric beauty standards are thought as objective.

All of her arguments seem impassioned, coming from a place of first-hand experience. As a black African woman in Hollywood, Nyong’o is uniquely qualified for a topic that has become an obsession of hers.

When she speaks of challenging stereotypes about black women’s looks, Nyong’o is not a tourist browsing through appearances. She does not also treat black women’s looks like exotic subjects of studies.

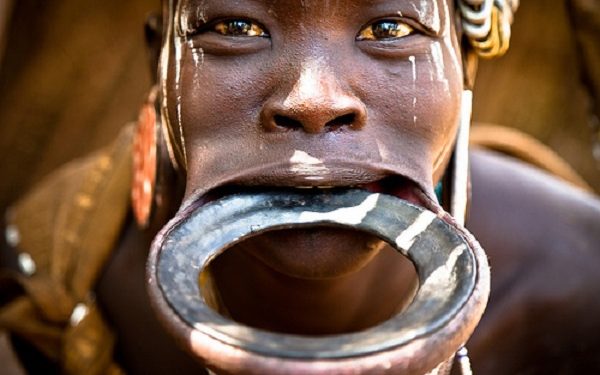

This is the attitude with which we are encouraged to view the much-publicized yet severely-misunderstood practice of lip plating. In a world obsessed with keeping the facial body parts slender, we can only truly understand lip plating if we are open-minded.

Some archaeological findings suggest that the practice of lip plates go back as far as 8000 BC.

One of the stranger things about the phenomenon is that different people in different parts of the world conceived their own forms of lip plating. The ancient Ethiopians and Nubians, as well as some indigenous peoples in South America, all invented lip plates.

There are a number of theories as to how lip plating was invented among Africans.

One holds that it was purposefully designed to make women look ugly so as to be unattractive to slave raiders. But the problem with this theory is that the practice dates further than slave trading was a definable enterprise.

Another theory speculates that lip plating is simply for beautification and showing a woman’s place in society. The theory adds that in some lip plating societies, the bigger the plate, the higher the social status of the woman.

This theory is also problematic seeing that in some of these societies, young girls are either married off or betrothed before their lips are cut.

Presently in Africa, the Mursi and Tirma of Ethiopia, as well as the Sara of Chad, may probably be the only known groups of people who still celebrate the practice.

More than anything else, lip plates have become the signifiers of the people’s identity. The plates distinguish the tribes from any others in the eastern region of Africa.

But it helps to know that the lip plate culture differs among the people. While the Sara will put the plates in their upper lip, the Ethiopian ethnic groups have it in their lower lip.

Lip plating among the Ethiopians has become the most famous in Africa, attracting both tourists and sociologists from around the world.

Among the Mursi, when a young woman reaches the age of 15 or 16, her lower lip is cut and held open by a wooden plug until the wound heals. The healing process could take up to three months.

But this is optional, contrary to the belief that lip plating is a rite of passage. It is the prerogative of the young woman to decide how she likes her lips stretched or if she wants a plate at all.

When a woman is determined, she could take up to a plate of over 12 centimetres in diameter on her lip.

So why would anyone choose to go through this conceivably excruciating pain?

According to African culture curator site Hadithi, lip plating is to its performers as opera is to Europeans.

Hadithi notes: “The lip plate tradition is valued by both parents because it indirectly means that the father’s number of cows will increase when he is paid her dowry. Any man who must marry a Suri or Mursi lady has to be wealthy because her dowry usually falls between 40 cattle (for the small plate) and 60 (for the large plate).”

For what it is worth, lip plating adds to vibrancy and variety of the African experience even if as students from outside may not understand it and simply appropriate the culture.

souce: Face 2 Face Africa